Africa 1979

My travels in Asia and Europe in 1976 and 1977 were starting to become a distant memory by 1979. I had been back in Canada for for about a year and a half, staying briefly at the farm in Manitoba, and then working near Toronto.

But it seemed that Canada was no longer my cup of tea. The winters were chilly and miserable, and my shift work precluded much of a social life. I enjoyed the outdoors there, plenty of hiking trails and camping opportunities. But something was missing. I longed for the friends, beaches and mountains of Australia, and I especially missed the lure of the open road. So I decided to chuck in my life in Ontario and plan my return Down Under. As I was only a permanent resident in Australia, I had to get back there within 3 years. My time would be up in November 1979. How to get there? When travelling through Europe from Asia in 1977, I had met travellers coming from Africa and heard their stories. It seemed a more difficult and challenging continent than Asia, and I was intrigued by the sense of adventure. So I might as well spend some time in Africa on my way back to Australia.

Because of the perceived size and difficulty of the continent, I forced myself to swallow my pride and do something I hadn't done before. Rather than attempting it solo, I would go with an organised expedition. Cost would be something slightly under $2000 Cdn, plus flights, not cheap by my standards but necessary to manage the dark continent. I would make my way to Kenya via London, and travel with British-based Exodus Expeditions overland via Kenya, Sudan, Central Africa, Cameroun, Nigeria, Niger, Algeria and back to England. From there I would fly to Australia, hopefully before my 3 year absence expired.

So in Toronto I organised the expedition and connecting plane flights, left work, and was on a plane to London on 21 June 1979.

I met Sylvia at the Heathrow Airport and we had a good few days in London. I checked in with Exodus regarding flights and expedition details, and saw some of the sights of London that I hadn't seen two years ago.

Kenya

(Click for map)An Egypt Air 707 carried me from London via Cairo to Nairobi. I remember a couple of hours or so chafing at the bit in Cairo airport, wishing I could go out and look around with my first feet on African soil, but being stranded in transit. A night flight got me into Nairobi airport at 06.30 on 24 June. I encountered another couple on the flight who were also on the same trip, so we shared a taxi into down-town Nairobi.

First impressions: The roads and the city seemed so "African", a bit run down and busy and, of course, full of Africans. Being formerly a British colony, there were lots of chicken and fish and chip shops, and language wasn't a problem. Black-market money changers were everywhere, offering up to 16 Kenya Shillings for sterling. I'd been warned not to trust them, so changed my travellers cheques at a bank for something like 12 or 13 Ksh per pound.

Our first stop was the agents for our expedition. We found the office and were advised that the expedition group, having started the trip from Johannesburg, was still on the way up here, somewhere in Zambia or Tanzania at the moment. So we would have a few days before they would arrive and pick us up.

My next agenda item was to search out some cheap accommodation. I consulted my not-long-in-print Lonely Planet Africa guidebook and found that grubby ramshackle travellers favourite, the Iqbal Hotel. A dorm room there cost 17.50 Ksh. It would have been OK except that it was noisy (typical for a cheap down-town place) and the water didn't run that often.

Nairobi was not a bad place, somewhat seedy in parts but cosmopolitan and nice in others. It had an air of vibrancy about it; there's always something to see. The climate was beautiful, relatively cool from the altitude. The shanty-town and markets along the river were fascinating, large areas of black tent-roof supported on poles with market goods and ultra-cheap restaurants in which you could get a rough meal of corn, beans and rice for I think about 3 shillings.

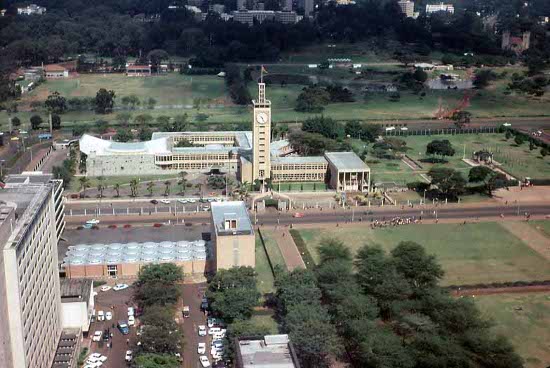

Parliament & Kenyatta's Tomb

The Kenyatta Centre, Nairobi's largest building, was worth a trip to its top for the view of all of Nairobi and surrounds.

After a day or two in the Iqbal, I got sick of it there and moved out to the youth hostel in the west of the city. It cost less and was in beautifully quiet and tranquil surroundings. Two things I remember about the walk from down-town to the hostel: 1. Many of the utility poles along the street were knocked down or damaged by bad drivers. 2. It was a slightly nervy walking home at night owing to reports of thieves robbing people at knife-point.

Dean, a neighbour from the farm in Manitoba, was working as a schoolteacher in a mission school somewhere out in north-west Kenya. With time to spare, maybe I should try to get out and find him. How to get there? I'd heard of people hitch-hiking in Kenya and it didn't seem all that bad. So one morning I packed a minimal amount of gear and hit the road north of the city. There were other hitch-hikers, mostly black, and they seemed to be getting the rides. I guess the shoe's on the other foot; I'm now the victim of discrimination. After an hour or two a truck drove past me and stopped to pick up a black guy a bit farther on. Well, let's try. I ran up to the truck and asked if I could get in too. Surprisingly the driver let me in; I guess he thought the other hitch-hiker could protect him from me.

The driver was going to Kampala, which was of course well beyond my destination of Kisumu. So it was a good ride, getting me most of the way there.

The highway out of Nairobi gradually left the city and passed through ever smaller suburbs and villages. Then suddenly we came to the edge of the Rift Valley. The scenery, mainly trees and buildings up to now, opened out to the vast expanse of the valley grasslands. The road wound interminably down, into increasing heat and onto the valley floor.

We stopped in a small restaurant in a village for lunch. There seemed to be only one item on the menu, a fried egg and chips, but that was OK. I paid for the driver's meal, having got the ride for free.

About mid-afternoon the truck let me off at the corner of the road to Kisumu. It was the middle of nowhere, just hills and fields and a couple of farm buildings nearby.

About a 20 minute wait yielded me another ride, an Indian guy driving in a car from Nairobi to Kericho. If I had waited in Nairobi longer, he may nave picked me up there. He was quite a carefree guy, making good conversation and driving quite fast. A third ride got me into Kisumu late afternoon. I checked into a cheap hotel (Sam's Inn, also in the guidebook) and got a dorm bed. I was the only white there. The only thing I distinctly remember about the place was a local woman there dressed in her underwear; she was obviously "in the game" and uncucessfully tried to proposition me.

Next morning I had to try to get out to the village of Roarua where Dean was living.

The most convenient transport was a Lake Victoria ferry going to Kendu Bay at 12.15. As I was getting on the ferry I came across a couple of westerners, a guy from New York (John) and an Australian girl (Pam). I started to talk to them in the hope they may be able to tell me how to get to Dean. Surprisingly (or maybe inevitably) they knew him, were his work colleagues and friends, and had heard about me and knew I was coming. They advised that Dean wasn't home at the time and was going to a village Mbita, farther west on the edge of the lake. Neil was also on his way to Mbita. So we got straight on a bus for a 5 hour trip Homa Bay, then a matatu (pick-up-truck transport) for 2 hours over rough dirt roads to Mbita. We headed straight for the mission there where Dean was to be staying. Unfortunately Dean wasn't there yet, not sure if he wasn't coming or just hadn't arrived.

The mission was run by a Dutch Father Tieland, interesting to talk to and get an idea of life in this remote community. He had a speedboat and a sail-boat to "go to work" along the lake-shore. Next day we were able to go for a short and enjoyable sail on the smaller boat, and I did some casual walks around the roads and paths. In Mbita I had a lunch of ugali (cornmeal cake) and chicken. Ugali is the staple of the diet here, and is a good if not exciting filler.

The following day Dean still hadn't showed up, so Neil and I went into the village in the morning to get a matatu back to Kandiege. A local guy whom we'd met invited us to lunch, where we stayed until 15.00. Before getting on the matatu we went into a small restaurant for a coffee. Meanwhile Dean had arrived in Mbita and gone to the mission. There they told him we had been there and just left. So he ran back into the village and was about to get on a matatu, when he found us in the shop. It was a real "Dr. Livinstone moment", elating to have found each other.

We all rode back to Homa Bay and spent some time looking around the markets and town. It was market day and the whole town was a hive of activity. The fly-blown butcher stalls provide 2 choices of meat: with bones or without.

We checked out the bus stop for a ride to Dean's place in Roarua. I was about to learn about African bus stops. Being late market day, everyone wanted to go home now. The buses were swamped. We watched as one bus (ours) drove up. As he approached the station, a large mass of people started to mob towards it. The driver panicked, turned around and gunned the motor to escape. Then he sat some distance away before getting the courage to return. Finally he drove into the station again. Masses of people thronged the bus, fighting and pulling at each other at the doorways to get on. Some people climbed in the windows and then had their luggage passed through. We gazed in awe at the spectacle and decided we weren't getting on a bus tonight. A quick check of matatus also proved fruitless, we could have chartered one but at an exorbitant price. Over at the mission in town the people there knew us, and they let us sleep there that night.

Next day were able to get a less crowded bus and make our way to Kadelle, then a 1 ¼ hour walk to Dean's home at the mission in Roarua. It looks like a basic but comfortable life here. We had good home-made pizzas for dinner. I had a good day or two visiting with Dean and exploring surrounding countryside. It seems like quite a pleasant life here.

I returned to Nairobi by ferry and overnight train, somewhat more comfortable and less adventurous than my outward journey. At 07.30 on 3 July I was waiting at the Kimbla office for news of my expedition, learning that it was due in about 3 days.

Nairobi gets boring rather quickly, it hasn't got the ambiance of the villages and I quickly run out of things to do. The Nairobi Museum has about 3 hours worth of archaeology and tribal culture. I changed money, bought a book to read, bought shoes and a mosquito net for the trip, got a haircut, toured the Kenyatta Building, Nairobi's tallest, and just explored the city. One evening, almost mad from boredom, a couple of us went to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. We almost didn't get in, not being alcoholics, but it was an interesting education when we did.

On the evening of 7 July, the expedition truck arrived from the south.

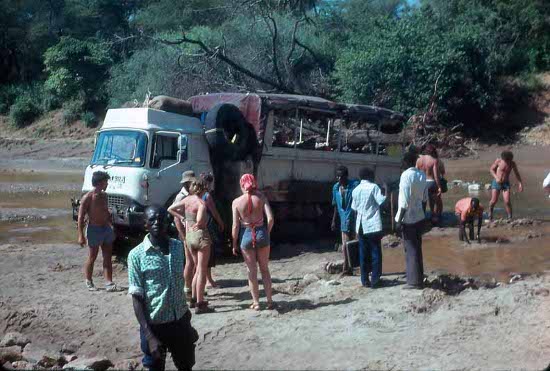

Expedition Truck

It was quite a thrill finally to meet our expedition coming up from Tanzania, seeing what the vehicle was like and seeing who I'd be spending my time with for the next few months. There were two drivers, Chris and Neil, both seemed OK people to travel with. The party numbered about 15 or more, mostly Australian, New Zealanders, Americans, Canadians and British. Some were about to leave the expedition; too slow/late just getting to Nairobi so would take too long to get to the end, and some seemed to think it was just "too rough a way to travel". Others like me were just joining. The truck was a 1953 model Bedford M ex-military truck. It had bench seats along the sides of the box, a steel frame & tarp box cover. All of the storage space was on the truck itself, no trailer. So it might be a bit crowded but OK.

Our first get-together was an evening buffet dinner at an Indian restaurant, good food, as much as we could eat, and a good opportunity to get acquainted with the party.

One driver was leaving the expedition to return to London, and another (also a Neil) was to come from there to replace him. We had to give him all our passports to take to London ( I think to get certain visas or something), and some people like me also had to get travel insurance. So we all had to wait in Kenya for a week or two until the new driver could arrive with our passports. What do we do with all that waiting time? A day or two would be taken up with maintenance and preparations for the onward trip. I remember a good couple of hours or so cutting up steel rod and bending it to make tent pegs for our 2-person A-frame tents.

With time to kill, we decided to take a couple of trips around the country.

Masai Mara

First was a trip to Masai Mara Game Park. Apparently the annual game migration from Serengeti was under way. So we all packed up our gear and headed north-west, along the highway where I had been several days ago. Down the long descent we went into the Rift Valley, with its vast expanses of yellowed grass. Shortly after the descent, we turned left off the main highway and down the secondary road toward Masai Mara. The drive from Nairobi took a number of hours, but we were starting to see more and more game animals even well before the park. Small herds of Thompson's gazelles were everywhere, as well as eland and giraffes in twos or threes. As we entered the park, we encountered vast rivers of wildebeest and zebra, the most impressive display of wildlife I had ever, or would ever, see. It was totally amazing.

We would spend a couple of nights camped in the public camp ground. It was a bit unnerving sleeping in the tents and hearing the lions roar in the distance, knowing there's nothing between them and us save for some distance and a layer of tent fabric.

Lion, Masai Mara

The two days or so were wonderful, driving around different areas of the park, seeing ever more vast numbers of wildebeest and zebra, as well as lions (including one in a tree above us as we drove past), elephant, buffalo, storks, baboons (mostly panhandling around the camp and village), hippos, gazelles, hyenas and vultures. We found we could easily find where the lions were resting, just go to where all the safari vans are parked in a circle.

Also quite prominent were the Masai people themselves, tall dignified looking men with their long robes, large earlobes and spears. They didn't take kindly to unauthorised photography, threatening members of our group with their spears at the sight of a pointed camera. Fair enough, just ask first.

We stopped at the swish Mara Serena Lodge and looked around there for a while. One of the guys lost his glasses and nobody in the hotel could find them. Only after he offered 30 Ksh reward did the receptionist remember that they were under the counter.

Back in Nairobi, we met the new driver Neil from London. We also had to get visas for Central Africa etc. I was getting somewhat antsy with continual waiting, always something else to do or wait for before we could move on. We were increasingly late with our expedition and some of the group already looked like not making flight connections at the end.

While waiting for CAE visas, we set out on our next excursion, south-east to Amboseli Park and on to Mombasa. We drove on the road south toward the Tanzania border, stopping for lunch at the Masai Training Centre, where we learned of their projects and handicrafts. At 16.00 we stopped briefly at the border town of Namanga. I looked longingly at the border, closed to overland travel because of some political dispute, and wished I could have gone across to attempt Kilimanjaro. But, on east toward Amboseli park.

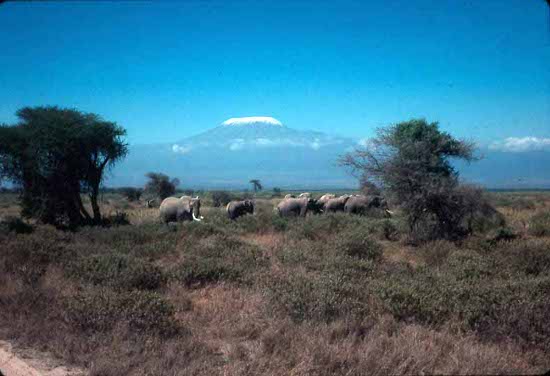

Elephants, Amboseli

Amboseli Park is known for its elephants, and we weren't disappointed. Herds of them were near the road in places, enticing us with postcard-quality photo opportunities, snow-capped Kilimanjaro as a backdrop. As we would drive near a herd of elephants, the bulls would move between us and the females and young, giving them protection from whatever threat we may offer.

On east back to the main highway and through Tsavo West Game Park. We didn't see a lot of wildlife in Tsavo, maybe just too vast to have dense concentrations of animals. Farther along, we passed through a lush green "desert" area, so called because at one time tse-tse fly rendered it uninhabitable by animals or man .

Mombasa has strong Hindu and Muslim influences, very bad roads and, despite some rain, a water shortage. We would camp a couple of days near the beach, explore the area, and get some welding and mechanical work done on the truck.

The main point of interest in town was the Portugese-built Fort Jesus, remarkably well preserved and full of tunnels, nooks & crannies.

A group of us decided to treat ourselves to a nice meal at a seafood restaurant. It was, I thought, not cheap at about $6 per person, but it must have been about the best seafood meal I'd ever had, well worth the price.

In the afternoon of the first full day, the group had to get back to the camp-site outside of town. Not quite everybody could fit in the matatu. So I volunteered to hang back and hitch-hike to the camp. It turned out to be a good move. I was picked up almost immediately by an Indian guy who lived not far from the camp. Instead of taking me straight there, he invited me to his home for a short while. It was one of those magical, "meet the people" encounters that we travellers cherish. Visiting with his family and having tea, I was able to learn a little about the culture of the Indian population of East Africa. It was interesting to hear that my host had never in his life eaten the local ugali (cornmeal) dish. It must have been "black man's food", and not in his culture. I also noted that it isn't uncommon to see whites associating with Blacks, but never an Indian associating with a Black. Again I guess a cultural thing.

Although I could have walked from here, the Indian guy drove me back to the camp. Two people are responsible for each day's meal procurement (using company money) and preparation, rotating daily. Dinner was about to be cooked, and it was my and my tent-partner's (Art) turn. We scraped together a very nice eggplant ratatouille and a stir-fry potato/vegetable dish, Art being a part-time chef. We were eating well these days; food was plentiful and good. We had no hint yet of the pinch-gut horrors yet to come later in the trip.

With the truck welded up, hopefully adequate for the next 3 months, and our passports maybe ready with CAE visas by now, we started back for Nairobi. At our speed the drive would normally be 1.5 days, so we would stop overnight at a Sikh temple that we knew of on the way. These temples normally accept guests, possibly in return for donations. There was plenty of room in a dormitory for us to sleep, so we didn't need to tent it tonight. A meal also was provided, consisting of dhal, vegetables, noodles and chapati; very good. In the evening a religious service was conducted, giving us some insight into that fascinating religion of Sikhhism. Later in the dormitory it was ground zero for the flatus storm, maybe too many guts with too much lentils. At least we all got a good laugh out of it.

We were back in Nairobi around noon the following day. But we still had about 5 days here waiting for things, more work on the truck, and final preparations before departing north and west across the continent. We were almost going crazy with the interminable waiting and always-something-else-to-fix.

One day to fill in the time, I found the East Africa Railway Museum near the rail yards. It had good exhibits of the history of rail in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Many steam locomotives were on display; my favourites were a couple of the massive articulated Garratt engines.

On the afternoon of 26 July, fully a month after my first arrival in Africa, we were off from Nairobi again, this time for good. Whoopee! 3.5 hours driving took us into the Rift Valley for my third time, on past my previous turn-off for Kisumu and to our first camp stop just before Nakuru.

A little about the truck: Travel was quite slow even on good roads because of the heavy load of fuel, water etc. Besides the inbuilt fuel tanks, we had two 44 gallon drums of fuel behind the cab atop the water tank, to get us through the anticipated long stretches without fuel. Two truck tires, one strapped to each side of the truck by the fuel drums, gave the vehicle an "elephant ears" look, a source of annoyance and amusement throughout the trip. Seating in the back was in the form of a bench along each side, so we sat facing one another. Personal luggage was stored under the seats, water jugs along the sides behind the seats, spare food in a cabinet in the front of the back, truck equipment in compartments under the back, and of course water in the tank between the back and cab. Sand mats and bits of firewood hung on the side of the back. We mainly sat in the back of the truck, but the daily cooks were allowed to ride in the cab (ostensibly to look out for food markets), and a couple of us were also sometimes able to enjoy the view from the top front of the back.

Camping was normally in open space anywhere we found that looked comfortable and deserted. Teams of two on daily rotation prepared the meals. Meals, consisting of food bought in markets or truck food, was cooked on an open fire using a sand mat as a cook surface, and served from collapsible tables. The tank water was chlorinated and raw vegetables were soaked in chlorinated water. Hygiene and food safety was good, as we normally only got sick in the cities. We slept two to a tent.

In Nakuru we had to strengthen some of the truck welding, which took us until 13.00. I amused myself by exploring the town, chatting with local truck drivers and clothes mending. Progress onward was slow from road construction. At (about) the equator we stopped for the obligatory photo op, but in those pre-GPS days, how are we to know where exactly it is?

Early on the following day we stopped on the shore of Lake Baringo to look at the flamingoes, but unfortunately we hadn't made an appointment with them, so no luck. On through Kito Pass, we were not yet ready to connect the 4-wheel-drive, so progress was slow, about 9 hours for 100 km. Still, I enjoyed the hills and thorn-bush scenery.

Lodwar

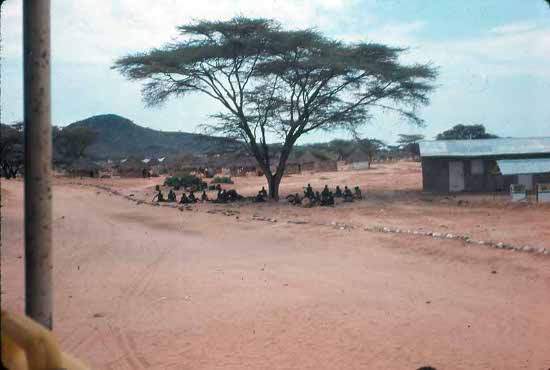

Lodwar was probably the last major town in Northern Kenya, with the last fuel station before Bangui (in Central African Republic), so we had to top up all tanks and drums with as much diesel as we could cram in. The only food available was potatoes, tomatoes and canned food. There wasn't much in the way of markets from here on, so we would be having to dip into truck food quite often through Sudan and Central Africa. My main memory of Lodwar was the big acacia tree in the centre of town, under which a large group of locals sheltered from the ferocious midday heat.

Roads were initially dry and easily passable, even through riverbeds. Eventually though we started to encounter mud had to connect the 4WD to negotiate riverbeds and mud holes.

When finding places to camp in the evenings, we generally found the most uninhabited places available, apparently nobody for miles. But then, along would come a group of Turkanas or whoever, to check us out and visit. Where do they come from, out of the ground? Anyway, despite not a word of common language, but with their long robes, hand-held stools and weapons-grade wrist bracelets, they were quite interesting, and friendly enough. They took their leave of us sometime in the evening, but next morning they were back to see us before we left. On leaving we would extinguish our campfire and bury any empty cans and bottles in the fire-pit. Then as we drove away we would see the locals uncovering the containers and taking them out of the ashes to use for themselves. So, a lesson learned; after that we always left our empties BESIDE the fire-pit.

On afternoon as we were looking for a camp-site, we met an Encounter Overland group coming the other way. It's always good to meet other travellers, an opportunity to get acquainted, compare notes and party on.

Lokichokio was the last town in Kenya. We went through exit formalities at the border post and camped shortly after. Curiously, we found leopard tracks in the morning near our camp-site.

We left Kenya on 31 July, about 5.5 weeks after my arrival.

Sudan

(Click for Sudan, Central African Republic, Cameroun, Nigeria and Niger map)As we drove into southern Sudan on 31 July, we came upon a sleepy, nondescript village not far from the border. We knew that we had to get to Juba before we could go through Sudanese immigration and customs. So as the Sudanese soldiers casually waved at us from their post in the village, we waved back and kept going. No problems. Until we were a few minutes out of the village observed an army truck roaring up very fast behind, full of very angry soldiers shouting and waving and pointing their .303 rifles. I guess we were meant to stop in the village for a police check. We threw out the anchor as fast as we could and performed some big-time grovelling and apologies. The soldiers escorted us back to the village in rather ornery moods, likely from having to use up precious fuel to chase us. Anyway we were able to get our passports stamped without going to jail or anything. Over the next several weeks police checks would be required in almost every village.

Throughout Northern Kenya and Southern Sudan, the roads got progressively worse and the countryside less developed. Into Sudan, we were entering "black cotton" soil, dark, organic and very slippery in the wet. It would prove to have some rather traumatic moments as we negotiated over it.

We were entering the wet season in this part of Africa. I had been looking forward to the challenge of fording rivers, getting stuck, etc., part of the adventure. But I very quickly learned not to anticipate these events with any pleasure; they were just hard work, worry and stress.

Stuck, Sudan

Sometimes when we started up, some of us would go for a walk ahead of the truck until it would catch us up. But one day the truck got stuck in mud before catching us. We had to walk back to find the truck stuck in a sandy riverbed. We extricated it with shovels, sand mats and elbow grease. Also crossing, and getting stuck in the process, were a couple of vehicles of Sudanese "hunters" (probably poachers). We were able to pull them across with our winch.

One day we came across a man and a boy beside the road. The man was holding a live chicken. We stopped and asked the guy if the chicken was for sale. He said "No, he's keeping it because his son is sick and he needs it to pay for a ride to the hospital. So our driver said "Okay, give us the chicken and we'll take you to the hospital". So we did, and with another chicken we bought somewhere else, we had a relatively sumptuous meal that night (at least if 2 scrawny chickens divided among about 16 people is considered good).

Next day, driving along a banked-up but wet slippery road toward Juba, we were struggling to keep the truck in the centre of the road and avoid sliding into the ditch. From behind us two trucks, driven by locals and loaded with lumber and passengers, were coming up much faster than we dared to drive. We were taking up the centre of the road so weren't sure whether or not they would slow down behind us. Of course not, that's not macho. Both drivers drove straight into the ditch to our left, kept their feet to the mat, and overtook us, somehow without getting stuck. Farther on, they found a place where they could get back on the road and keep going. Boy those drivers are good(??).

As they receded in the distance we could see the two trucks drive down and across a concrete causeway river crossing. The first truck made it up the other side, but the second one stalled going up. Without brakes, and unable to get back into gear, the truck careened back down to the river, off the causeway and flipped into the water. Lumber and people were flying everywhere. As we caught up to it, and the first truck turned back, we saw that the truck was on its side in several feet of water. Some people were swimming and crawling to shore or the causeway, while others were evacuating the cab and handing a baby out through the door. Lumber was spilled out of the box of the truck, pinning below it a man in a military uniform. Only his lower legs were visible and the rest of the body was under the lumber and truck box, below the water level. I don't know to this day whether any other bodies were invisible totally below the lumber or truck.

The scene was total chaos, nobody was in charge. It was unlikely that the person pinned was alive but it fell on our group to organise the crowd and start to move the wood and try to rescue him. It took quite a while to move some lumber but we still couldn't pull the body out up to the time the police arrived. At that time we wanted to leave, but the police asked us to stay until we could extricate the body. After much more transfer of lumber and repeated attempts to lift the truck box, we finally got it high enough to pull the unfortunate soldier out, his neck obviously broken.

Back in our own truck, and preparing to drive on, one of our group was able to find a bottle of whiskey in his luggage, passing it around for a much needed drink. Definitely not a pleasant day.

From the near-desert of parts of Northern Kenya, the land was becoming increasingly lush with more villages, crops and livestock. Large granite hills poked out of the plain. Situated on the White Nile River, Juba is the principal city in the south of Sudan. Even though we're already nearly halfway across the country, it's where we have to stop for Sudanese immigration and customs checks before proceeding west towards Central Africa.

Our first priority was to give our passports to the officials, to go through the immigration process and allow us to continue onward as soon as possible, hopefully next day. However, we have to remember we're in Black Africa now, in sovereign, independent nations. We're the whites and here we don't have the power; we suck it up and wait as long as it takes. They must have been looking for baksheesh, and we weren't prepared to give it, so we couldn't even get a commitment from them when we could get our passports back. Repeated trips back to the immigration office elicited responses like "Not ready yet" or "The guy hasn't come yet, come later". In the end it took 2 days before we were allowed to leave. It wouldn't matter so much except that we were already behind schedule to complete the trip, and there are better places to kill time than in an axilla like Juba. I remember at one stage watching one of our group furiously chopping firewood with an axe to vent his frustration, presumably trying his hardest to resist the temptation to use the instrument on some of the officials.

Juba must have been one of the most dreary, smelly and decaying cities on Earth. Apart from a small number of threadbare grocery stores and tailors here and there, and a wharf along the river with a few warehouses and a few people unloading bags of food from barges, there was no evidence of any commerce or industry. A nearby airport had no activity or aircraft, save for a lone C-130 that looked not to have been used for a while. What do the people do here, what do they live on? We heard that there was a cholera epidemic around, so were afraid to eat out.

As for points of interest, the Nile is big and beautiful at this point, impressive even this far upstream. We were camped in an open area near the river, so were able to take advantage of the pleasant river scenery. Somewhere in a city park is a small memorial to prominent white 19th century figures; Burton, Speke, Gordon and Emin Pasha if I remember right. This was the only cultural or historical facility we could find in the town.

Dinka Dancers, Juba

On one day of the week the local Dinka tribe engages in a dance evening in an empty area outside of town. It's not a tourist thing (no tourists here anyway), but more of a "pick-up" activity for the young guys to show off their talent and hopefully latch onto the girls. So on our first evening we went to the Dinka Dancing. The guys, dressed in zebra-skin loincloths, danced in conga-line fashion, snaking in and out among the rest of the crowd. The girls mingled on the edge or amongst the crowd, presumably picking out whomever they fancied. I joined in for some of the dancing but wasn't rewarded with any female approaches. Still it was educational and entertaining.

Passports in hand, and stocked up on food as much as we could (given the paucity of food in the stores), we were eventually on our way west. The road from here became progressively even rougher, more remote and less travelled. Our road was bordered by forest, with villages and small cleared areas for manioc or bananas.

The local Sudanese are usually friendly, waving and smiling as we pass. Foreigners here are a real novelty. Shops have very limited wares; beans, onions, potatoes, manioc, a few tinned foods, matches, fabrics and a little hardware. We were starting to use up a lot of truck food and our meals were getting smaller. Hunger would affect our moods and add to the angst of the trip.

One late afternoon we were starting to look for a place to stop for the night. Entering one small village, we stopped near a local man to ask him if we could camp anywhere nearby. As we tried to speak to him, he looked at us with terror, turned and ran in the opposite direction as fast as he could. Obviously he must not have seen whites before at such close proximity, and must have been in fear of being sold into slavery or something.

Even way out here, we come across the occasional foreigner trying to get through independently, possibly taking days or weeks to find transport. At the Sudan border a French traveller found us and persuaded us to give him a lift for a few days. If we hadn't happened along I don't know what he would have done.

After about 9 days in Sudan, we were passing through to Central Africa.

Central African Republic (or "Empire" as it was then called)

On arrival at the border between Sudan and Central African Republic, exit formalities from Sudan were quick and painless. But the view ahead was discouraging. The "road" seemed to end there, and the only way west was what looked like a little track heading into the jungle, not much more than a hiking trail, and barely able to accommodate the width of our truck. This was the "Trans Continental Highway" on which we would have to traverse the length of CAR. (By the way, were were going this way rather than west from Kenya because the border with Zaire was closed and there was no other way through).

I remember vividly the roughness and narrowness of the road. For several days we were rarely able to drive at more than a walking pace. Some days, at the start of the day's drive, some of us would walk ahead of the truck for exercise. But we would invariably have to stop somewhere after a while and wait for the truck to catch up.

The first border day and the next day or two would be the most difficult and depressing of the entire trip. Some of our group, those who knew we were too far behind schedule for their liking but hadn't left from Nairobi, would have liked to abort the trip now, but had no means of escape.

We have to fill up our water tank frequently, and on our first day in CAR had to stop to fill up shortly after the border. The only source was a pond or creek near a small village, the locals pointing out where it was. Trying to get close to the water with the truck, we got in trouble with a local woman for driving onto her vegetable patch. The water turned out to be the most vile, necrotic slime we'd ever had to contaminate our tank with. We did manage to fill our bottles with the grey liquid, and bucket-brigade it to the truck, but even with double chlorine and boiling it up for tea, it was still almost undrinkable. One more nail in the coffin of our morale.

We entered the country without any CAR currency, and wouldn't have access to any for at least a week or two. So throughout most of the traverse of this vast country, even when we did stop at some of the sparsely stocked local village markets, they were generally not much more than a few women sitting on the ground with a little ocra, peanuts and tobacco around them, not seeming to care much whether they sold anything or not. We found it difficult to buy enough food to keep us going. Occasionally we were reduced to pawning personal pen-knives or somebody's US dollar for some food. Along this stretch, dinners were mostly truck food. We were always hungry, even after dinner. Craving bellies make ill tempers, and there were more than the occasional dispute or altercation. The last of our coffee marked one ratchet-up of our collective stress level. At least we had no fistfights, despite having heard of them on other trips.

Thus, our first camp night in CAR was somewhat tense, some of our group berating the drivers for not having any local money, the bad water, the lateness of the trip, the roughness of the road and whatever other complaints, as if the drivers could do anything about it.

Bridge, Central Africa

On our first full day in CAR, not long on the road, we came to our first "bridge" in the country. It was simply several logs, flattened on top, laid across a creek. We dismounted from the truck as we crossed, to minimise the truck weight. No problems this time. The next bridge a few km farther looked similar. It looked safe enough to cross so we all stayed on the truck as we slowly drove across. But the weight of the truck spread the space between two logs, and the back wheel fell between the logs, with the axle then resting on a log. The whole thing looked pretty grim. How would we ever get out of this? At great risk of the logs breaking and the whole mess crashing to the creek below, we had to gingerly jack up the axle on one of the logs. We got it up far enough to pull the logs back together again and let the wheel back down. It took 4 hours but we were finally able to drive off the bridge. From then on we dismounted for all creek crossings and placed sand mats across any log gaps.

Later in the day we came across another bridge, in even worse shape than the last. We decided in this instance to destroy the bridge, put the logs into the creek bed, and ford the creek. This operation also took a number of hours. I pity whoever next tried to cross that creek. That day we accomplished a total of about 22 km, a fact that contributed to another depressing evening.

For the first several days at least, in the remote east of CAR, our road was, as mentioned, narrow, rutted and rocky. As we drove along the open sides of the truck would scrape heavily against tree branches that were growing over the road, sending showers of an incredibly diverse range of leaves and insects onto our laps. "Hey look at this bug! Ain't she a beauty?"

Of more serious concern was the ubiquitous presence of what looked like tse-tse flies or deer flies, vectors of some rather nasty diseases. We were constantly vigilant for them landing on us, trying to swat them on ourselves or our companions before they bit. "C'mon, put a bit of muscle into it; don't be chicken!"

This portion of our trip was at the peak of the wet season. Rain wasn't a real problem in that it didn't come down often enough to drench us. But the roads were often slippery and we came close to sliding off the road on more than one occasion. Our firewood was usually wet as well, and at our camp stops it became a significant accomplishment sometimes just to get enough of a fire to cook.

Beyond the first major town Obo, the road improved slightly and we could make better time. River sizes increased and log bridges gave way to manned ferry crossings. It rained frequently though, and when passing through villages like Kitessa, the police sometimes made us wait an hour or two for the road ahead to dry out. At Kitessa we managed to buy a couple of chickens, and later when camping a passer-by gave us two more; the best feast in days.

One evening, camped in the forest somewhere, a group of locals with a small herd of sheep came past our camp. We started chatting with them within the limits of the language barrier. Our goal was to try to barter whatever pen-knives etc that we had for one of their sheep. Lots of smiling, cajoling and haggling failed to result in any workable deal, but it was a fun encounter anyway.

We didn't see a lot of wildlife on this leg of the trip, at least probably a lot less than what saw us. Occasionally from our tents at night we would hear the roar of a leopard or some other animal a short distance away. Later, as the countryside opened up somewhat, we caught a glimpse of a couple of elephants, covered in red dust, sauntering along the edge of the forest.

At the town Zemio, a few days into CAR, we visited an American mission run by Les and his wife and two kids and their pet chimpanzee. It felt like the "Daktari" TV show. In such a remote place as this, meeting up is good for both parties. We talked for some time about the country, roads, the economy and politics, a first-rate education of what it's like to live and work way out here. Les was not a doctor, but many locals come in with frightful sores and illnesses, including things like hernias that he has to perform surgery on, "it's all mechanical stuff, pretty straightforward". You've got to admire these guys. We had seen the wreckage of a C-47 aircraft near the road somewhere earlier, and Les told us it's pilot was in jail for having destroyed a third of the CAR Air Force.

At the village Barh we had to stop for the usual obligatory police check. We were told by the local authorities, owing to the rain, the road ahead was impassable and we could go no further. What's this? Coming half way across Africa and we had to turn back? But more talk and negotiating eventually led us to the conclusion that they were probably just out for some baksheesh. Sure enough, a bribe of a couple of litres of diesel fuel soon had us on our way again. In fact, the road ahead was no worse than what we'd already been on. Next day at the village Dembia we again had to bribe our way through the rain barrier. Apparently its common for the villages to use rain barriers as commercial levers.

At the river in the next town Rafai, we were told that the ferry winch cable is broken. We had to camp in town as Chris our leader crossed the river to go to the mission there and see if the missionary Ray could help. Next morning we all met at the river and Ray helped work out that the cable was only weak. We had to donate a couple of cable clamps and 1000 CFA (the local currency) to get the truck across. As I was behind in town shopping for food, I missed the ferry crossing, and a few of us crossed the swift-flowing river in a dugout canoe, great fun.

At the mission in Rafai, we dropped off some supplies and mail that we had been delivering from Nairobi, so our arrival was a bit like "my ship coming in". As expeditions like ours is their only contact with the outside world, the joy of meeting worked both ways. We stayed all afternoon and overnight. They put on a wonderful dinner of rice, palm nut stew and chocolate lush dessert. We talked and worked on jigsaw puzzles all evening, a morale-boosting break from the rigours of the road.

On day 10 of CAR, Bangassou was probably the largest town we'd come to so far. Even though we arrived early in the morning, after shopping in the market (they sold inter-alia manioc (a type of cassava), grubs and elephant meat) we decided to call it a day here. I explored around the run-down but friendly town in the afternoon, practising my French with the locals and looking in on an open-air marriage ceremony. Along one street some people invited me into their house for a taste of their manioc wine. They were pretty blotto and we had a lively conversation in French.

Kembe Falls

Day 12 saw us at Kembe River and Falls. I hadn't been to Victoria Falls, but this one, though nowhere near the scale of its much more famous sister, was still quite impressive. The roar of the huge volume of water cascading down a considerable precipice, still rings in my ears. We crossed the river on our first steel bridge.

Wet rutted roads and rain barriers continued to impede our progress, but as we progressed west it became less remote. We started to get to places where we could more easily change money and buy things like bread. Crops like tobacco, cotton, tea and coffee were more common. As I walked along the road one day someone gave me a gift of mandarins and peanuts.

Shortly after the Kembe River, we got another boost to our sometimes flagging spirits. We came across a wide, shallow stream. Unlike the muddy, putrid creeks we'd been using up to now, this one had wonderfully clear, clean water, evidently spring fed. Words can't describe how beautiful it looked. Off with the clothes and in for a refreshing swim and bath. We emptied out all the cloudy water from our water tank, and filled it up completely with the clean water. Never know when we'll get water like this again.

In the middle of a good 154 km day, we passed through the large edge-of-desert town Bambari. Buildings were pointy-arch stone or brick structures, more reminiscent of Chad than the jungles of the Congo. It was the biggest town yet in CAR, with a few bars, shops, and empty fuel station and even a bank.

The next stop, the town Sibut, the last town before the capital Bangui, was another milestone. From here the paved highway started again, our first since Central Kenya. Wow. Up onto the pavement, only maybe a hundred miles or so to Bangui, and enthusiastic yells of "Let's Haul Ass!" The elation lasted about 2 minutes, as the motor suddenly cut out, leaving us stalled beside the road. We still had a small amount of diesel fuel left in the tank, but the fuel line was above the level of the fuel. I guess there were just one or two too many fuel bribes back along the way. The only place where diesel was available was in Bangui, the capital, and we weren't there yet. We had to limp back into Sibut and look for fuel. After much looking around and negotiating, we finally were able to buy, at an extortionist price of a dollar a litre, a small amount of kerosene. After mixing it with some motor oil and pouring it into the fuel tank, we were on our way again.

It was late afternoon before we approached Bangui so, instead of going straight into the city, we set up camp about 20 km before. We wanted to get into the city at the start of the day, with plenty of time to get organised. That evening in our bush camp was distinctive for the fantastic light show from a lightning storm passing by in the distance.

Next morning, 25 August, we were in Bangui, quite a cause for celebration. The worst of our trip was over. This was the first major city since Nairobi, large buildings, restaurants, coffee shops, boulangeries and patisseries, drinking establishments, and generally more "civilisation" than we'd had for quite a while. We'd been about 15 days in the jungles of CAR, and over a month since Nairobi.

At K12, before the city, we checked through immigration (as in Sudan, why bother, we're most of the way through the country already).

We found an open, grassy area near the river to set up camp. Chris and Neil started the process to buy truck fuel and other necessities. Some of our group, sick of camping, gravitated to the first hotel rooms they'd had in weeks, while I stayed in the camp. I was able to change some money (475 CFA to the Pound), pick up a couple of letters at the poste restante, and have lunch in a real cafe. Chris received a telex from the company complaining about the slowness of the trip and over-expenditure, which depressed him, and saddened me as I couldn't see how we could have done much better.

With access to CFA currency, we could get good restaurant food. On the spit overlooking the Ubangi River was good French restaurant, serving among other things an 1100 CFA garlic chicken dinner to die for (but then at that stage of our trip most food anywhere would fit that category). Numerous shops sold wonderful breads and cakes. However, from eating out a lot, I did eventually get the runs off and on for most of the time here.

On Monday a group of us took a taxi out to K5, the African District, to shop and explore the big noisy bustling marketplace full of flies and dirt, easily the most vibrant part of Bangui. Later we checked the small museum with its good cultural exhibits. Night life, such as it was, seemed to be mainly in the up-market hotels and bars. But a good relaxing day could be spent by a temporary membership in the Rock Club, swimming, lying around and talking to expats.

CAR, or Central African Empire as it was known as at the time, was at the time run by Emperor Bokassa, an IdiAmin-type of chap not known for his liberalism or democratic tendencies. It was by any standard an oppressive dictatorship, and one in which the ruler apparently felt some dearth of security. There were military guards outside every vaguely military or strategic installation. In fact, a few weeks later when we were in Niger or somewhere, we got the news that Bokassa had indeed been ousted in a military coup.

We were in Bangui about a week. During much of that time, for activity, I would wander around exploring different parts of the city. One day I walked past the downtown area and out towards the other end of town, downstream from where we were camped. On the main street I passed the radio station with the usual guards, and kept on going. I walked as far as I wanted to and then started back. I saw that the river was nearby so thought I'd walk back to town along the river edge. That path took me parallel to the main street, and I eventually came by the back of the radio station. A couple of soldiers saw me, came over, and shouted "Halt! Ou Allez Vous?". I replied that I was just walking along the riverbank to go downtown. Well, I guess I was big-time not supposed to be there. I was promptly put under arrest and escorted, of all places, into the radio station.

The station had what looked like some prehistoric radio equipment, far too old to be of intelligence value, so what's the big deal? They plunked me down at a desk and started to search and interrogate me. They saw that I had a camera on me as well as a Swiss army knife and my wristwatch, all of which they confiscated. "Aha, camera, espionage!" Not very reassuring. These guys were obviously grunts looking to emphasise their self importance and show their effectiveness in nabbing insurgents. They pumped me with questions and accusations as to my identity and what I was doing here. When scared shitless I amazed myself how fast my school French came back to me, and I was able to converse rather well with them I thought. But I was warily looking around, wondering how I'd ever get out of here. What's the food like in prison and how many rats would be in the dungeon? How could I ever get a message out to my family, or even to the rest of my group?

As things settled down, I asked if I could go. No, we had to wait for the Colonel to come and talk to me. They offered me a bit of bread to eat, which I politely declined, having an unsettled gut from yesterday. I settled in to wait for the afternoon. My watch and pocket knife were still on the desk, and I slowly and casually put them back on, surprisingly without any objections. They kept my camera though. I spent a bit of the time standing or sitting on the doorstep. I momentarily had the colossally stupid thought of seeing how far I could get if I made a run for it.

Eventually the Colonel did arrive, a big quintessentially black-military-type, in a Peugeot 504 and a crisp uniform. He did speak some English, and questioned me in that language. He turned out to be quite a good guy, nothing to prove. He knew about our truck in town, and that I was one of the group. So, after he had all the details he needed, I had a ride back to the truck in his car. It caused quite a stir when my group saw me coming in a military staff car. I was released back to my group, even getting my camera back minus the film. That was a bit of a let-down, as the film roll was nearly full with a couple of weeks of pictures. But I was assured by our group leader that I was exceedingly lucky to have lost only a roll of film. Back at our camp I could regale the others with my tale of adventure and danger.

That may have been the end of it, except for one brief epilogue. Later that evening, who should show up at our camp, but the Colonel again with his car and driver. He was just returning my camera film which he had decided was not a security risk. Wow, what a great guy. After my profuse expressions of gratitude, we asked him to join us for a coffee, but he politely declined and went on his way. Weeks later, when I heard about the coup, I wondered about him and hoped he didn't come to harm from it. I don't know to this day, and still hope.

For the rest of the stay in Bangui, I did do other walks around town, but now with a renewed sense of caution about where I went. I kept a wide berth around anything that was guarded or looked remotely strategic.

Late on 31 August, with replenished fuel and supplies, we completed departure formalities at K12, left Bangui behind and forged on westward. Rain came and the road again deteriorated for a few days, sometimes limiting our daily distances.

Market, Central Africa

On through Bossembele, Yaloke, Bosemtele, Bouar, and to the border. In this part of the country we encountered a number of trucks broken down or bogged. One truck on its side had a full load of beer. On another stretch, a truck was overturned on the road, blocking it. Some of the people had fixed the road so others could drive around it. As we tried to pass, they wanted money to let us through. We refused and had to "run the blockade" by force.

This part of CAR was more prosperous and civilised-looking than the east. The countryside was mostly rolling open agricultural land, with some hills and good views. The markets were well stocked and we were able to eat reasonably well. We could even get meat (400 CFA/kg) some places, a real treat. The trick here was to get to the markets in the mornings, before the flies and heat had got to the meat. The people here, and later in Cameroun, were cheerful, healthy looking and well dressed. Every market, with its brightly dressed women and wonderful variety of foods, was a visual treat. Islam is becoming more dominant.

At Bouar a group of us went for a two-pub crawl, having a great time until about 11.30. I didn't drink much, having a bad gut at the time, but the others had a noisy rowdy release.

We could pick up Cameroun visas at Garoua Boulai, finally making our way across the border about 16.00 on 5 Sept. We'd been 28 days in CAR, easily the most difficult and taxing portion of the trip, and we'd survived.

Cameroun

This country was better off economically than CAR, and our fortunes regarding food and highway passage steadily improved. The people, like in western CAR, were pleasant and sophisticated. This was one of the more enjoyable sections of the expedition.

Just across the border, we were able to drive farther in 2 hours than we usually could in a whole day in CAR. It was still wet with the occasional rain barrier, but the waits were much shorter.

Lac Tison, a 300 m wide picturesque crater lake, lies just off the road before Nagoundere. We drove up to the crater edge, and were planning to camp down at the lake, but it was cool and wet so we had to settle for pictures of this scenic spot.

Ngaoundere itself was a nice little city with the usual boulangeries and patisseries to satisfy our cravings. I found and bought a couple of bars of Lindt chocolate, pure heaven.

Another blessing was the paved road from here on. We did 450 km next day, the best distance in a long time.

Towns, like Benoue and Garoua, are much better maintained than those in CAR, with big markets full of a great variety of foods and colourful women. Climate here is becoming drier and vegetation more sparse, more like the thorn-tree country of northern Kenya. Cotton and millet are grown on the arable land. Maroua in the north of the country is smelly and grotty, but with interesting markets and a population of resident vultures. At one market was a large group of people and drums playing. It was some kind of lottery, selling little packets of money rolled up in newspaper.

Moving on from the town Mora, we got a bit lost for a short time in the north of the country, ending up at Wasa Park and losing a couple of hours before finding our way to the Nigeria border.

But we were at the border about 19.00 on 8 Sept, not a lot of time in Cameroun but a pleasant little country.

Nigeria

This is the first English-speaking country since Sudan, so communication became somewhat easier. But the people here seemed more arrogant and less sophisticated than in Cameroun, and the country itself seemed more corrupt and less well run.

Our first "encounter" there was just as we crossed the border and were negotiating Nigerian Customs and Immigration. We asked "How'd it go?" when one of our drivers came out of the border office looking a bit disturbed, and he said "OK, if you don't mind getting a gun in your face." Apparently they were asking if we had any firearms on the truck, but with the official's accent, Neil couldn't understand what he said, and the official pulled his handgun and thrust it in Neil's face to show him.

The land was becoming progressively drier and more desert-like as we progressed into Nigeria. As we got away from the border the roads were paved and fast. We passed through villages Bama, Madiguri, and Kari but, not having Nigerian money yet, didn't stop to buy food. It didn't take us long to get to Kano, the main city in the north of Nigeria.

Kano was a major stop for us, the place to check on money that had been wired to us from head office, buy more fuel, and check out the sights. The money turned out to be waiting in Niamey, Niger, not here. We camped out of town at the racecourse, coming into town for restaurant meals, business and sightseeing.

Kano was big, crowded, hot and busy. A lot of oil money was being spent in a hurry and there were far too many vehicles in the streets. Meals were expensive. The Nigerian Naira was about 1.24 to the Pound, a restaurant meal was 1.00 to 1.80, ground meat in the market was 3.60 per lb, and eggs 2.20 per dozen.

As we were considerably behind schedule at this stage, some of our group would have been late getting home if they came through to Europe, so we had to put them on a plane here. That meant our group moving on was slightly smaller. Chris got yet another letter from head office complaining about the delays and expenses, which put him into some degree of nervous depression.

Dye Pits, Kano

Kano has an old city containing possibly the largest market in all of Africa, a vast area containing shops and stalls of every conceivable kind. We spent a couple of hours wandering around the walled city and market, looking at the meats, produce, dry goods, fabrics, hardware, and one section entirely devoted to the fez-type hats common in the region. Near the market were the dye pits, a series of large brick-lined holes in the ground that the workers filled with water and dyes and soaked the fabrics in. Nearby were the dyed materials hanging to dry. The pits were in clusters, each cluster with its own dye colour. They apparently couldn't put different colours in adjacent pits, as the colours would migrate between them.

Leaving Kano on 14 Sept, a Friday, we had to wait nearly an hour before being allowed to drive past a mosque, prayers in progress. North from Kano, we were getting into the Sahel, dry, scrubby, rocky and diabolically hot. Round African-style huts were giving way to square dwellings. In Katsina we picked up another traveller on his way to Niamey.

Next morning we crossed the border into Niger, having been less than a week in Nigeria.

Niger

Niger was even more desert-like than Nigeria, and just as hot. We were back into French-speaking territory. Niger appeared less corrupt and chaotic than Nigeria. Border formalities were forgettably benign.

Our route should take us essentially north through Agadez, linking up with the main north route to Algiers. But of course we had to go through the capital Niamey in order to satisfy government formalities. So up we went to the nearby town Maradi (no stop there because no local money yet) and west. The road was good and we made the distances well.

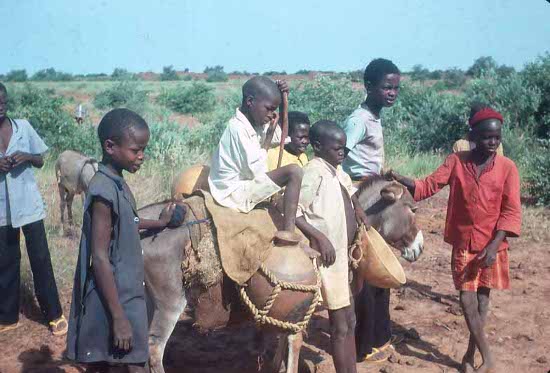

Kids, Niger

Until, that is, we started to see an unusual amount of smoke coming out of the exhaust and a smell of incompletely burned fuel. A stop near the road soon gave us a verdict of worn engine valves. We weren't going anywhere in that condition, so we set up camp then and there. The rest of the day, into the night, and next morning were taken up with ripping the engine apart, replacing the head gasket and other repairs. Luckily our two drivers were excellent bush mechanics and we had adequate spare parts. With all our help, the truck was back together in the morning and we were on our way. As we were preparing to leave, a small group of curious local boys with a donkey came by to check us out, passing on after a few minutes.

The small, near-border town of Birni-n-Konni was a short stop for cokes. Near the market was an older guy with a camel. Frank couldn't resist trying out the beast, so a few minutes haggling and an offer of a pen-knife yielded a whoopee ride for a hundred metres or so, lots of kids trotting aside laughing it up.

The truck still wasn't right, valve problems, so we drove fairly slowly and didn't arrive in Niamey until morning of the following day. Not knowing exactly where to camp, we found the racetrack outside of the city and set up camp there. It seemed a convenient place to stop as there didn't seem to be anyone around. But at night, after we were in bed, a group of military people descended on us and let it be known that they took a very dim view of our choice of camp-site. We had to pack up, were escorted to a police station, and thence to a commercial camp-ground about 5 km from town, costing about $4 each per night. I was now able to sleep outside at night with no mosquito net, very pleasant. There was nowhere to swim in Niamey, so liberal use was made of the campsite showers, our "vertical pool".

The capital Niamey was a medium size city astride the River Niger. With some sights it's not a bad place to spend a couple of days. We would get our Algerian visas here. Restaurant food was slightly expensive again though, 400 to 500 CFA for a meal. I spent some time in pubs with 150 CFA beers writing postcards, too hot for much walking. Two of our group had to fly out from here, so we had a restaurant meal and saw them off at the airport.

Niamey's main attraction was what was said to be the world's largest open-air museum and zoo. Covering several acres, it consisted of a series of enclosures with animals, displays of local culture and artefacts, exhibits of weaving and other craft activities, natural history and botanical exhibits. One cattle skull had the biggest horns I'd ever seen. Also on exhibit was a dead tree, apparently a famous one that had marked a desert waterhole somewhere out Bilma direction, and now on display here. As the museum closed at noon, I went there on two days to see everything.

I wandered down to the river on wash day, or maybe every day is wash day. The river bank was a kaleidoscope of colour from the multitude of people washing clothes in the river and spreading them on the bank to dry.

Niamey was also where we experienced our first sandstorm (or was it rain and wind; I don't remember). It just happened to come upon us as we were relaxing in an outdoor coffee shop down-town. Even there it was quite an experience, swift (only 10 minutes or so) and brutal. Visibility was almost down to zero, the wind ripped at awnings and the contents of tables, and sand of course got into everything. Later back at the camp-site we discovered that the storm had blown down all tents, ripped some, and caused other miscellaneous damage. Apart from losing a couple of tent pegs, everything was repairable though.

From Niamey we headed back east to Birni-n-Konni, north to Tahoua and north-east toward Agadez. The road was not always paved and was sand in places, making for some hard going. It was here that we had to re-connect the FWD drive shaft. It's amazing how solidly one can get stuck in a few inches of sand. On one rough stretch of road, a firewood log fell off the front of the truck, the back wheel went over it, a tire was punctured, and we lost a half hour to change it.

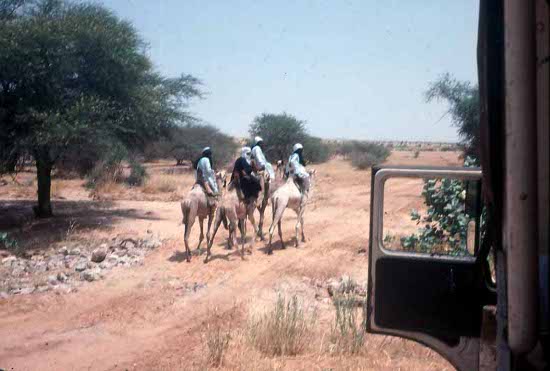

Touaregs, Niger

We started to meet our first Touaregs "in the wild". They were camped outside towns with their hides or cloth roofs on poles, or passing us with herds of camels, donkeys and goats.

One lunchtime as we were stopped beside the track, Several of the "blue men" came by on their camels. It was a bit nerve wracking, having heard of the possibly lawless nature of some of these people (think "Flight of the Phoenix"). Their unsmiling faces didn't help much either. Anyway, we waved at them as they passed and they rode on without incident. With their blue robes and covered faces, they are certainly impressive looking people.

At another lunch stop, three Touaregs brought us some firewood, so we shared tea with them and gave them a ride to the next village.

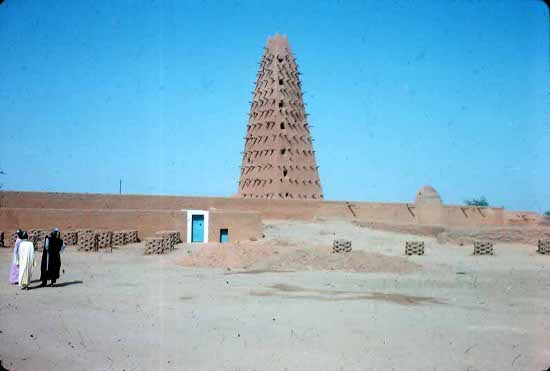

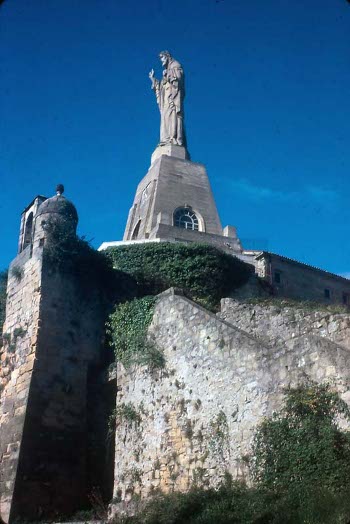

Mosque, Agadez

We entered Agadez on the afternoon of 24 Sept. Agadez is the main town on the northern edge of the Sahel, as one goes north toward the Sahara. Looking a lot like what I would imagine Timbuktu to be, it was quite an unforgettable place. It is mostly mud brick buildings and open markets, with a large and impressive Sahara-style mud brick/log mosque. The town is on the east side of the main highway north; on the west side is a large Touareg encampment/shantytown. I would have liked to wander through the Touareg village but wasn't sure how welcome I would be or how safe it was. So I stuck to the main part of town.

The only place to stay in Agadez was a public campground about 7 km northeast of town. It was OK except that we had to plan our trips into town to coincide when the truck was going and returning. The camp ground had a swimming pool, the filthiest I had ever seen. I don't believe it was ever drained or cleaned, just replenished as it evaporated. The water was therefore a grey soup with several inches of muck on the bottom. We swam in it of course, being so hot and nowhere else to swim, but were careful not to get our heads wet, and always shower afterward.

Agadez is also known for its silversmiths, fashioning their distinctive silver crosses out of the metal from old coins. Several of us visited a silversmith in his mud hut, haggling to buy a cross of Agadez or other souvenir. I bought a cross of Taouha for 1300 CFA. I also picked up a pair of camel-leather sandals for 1000 CFA, from which I later got considerable use.

My day to cook, I could only find high priced potatoes, onions and bread in the market. I avoided the meat because of the expense; it seemed to cost a lot more here than further south.

As we drove north from Agadez, the road again got progressively worse, deteriorating from pavement to hard surface to kibble, sand and rock. The land contours evolved from rolling hills and undulations to a vast featureless ocean-scape of fine rock, punctuated by massive dunes.

The word Sahara is I think a Berber expression, meaning simply "the desert". One appreciates this logic, because once you've been here, there is no other desert. It is simply so vast and unique as to defy imitation. Most of its surface, at least the part we drove over is fine rocky kibble. Impressive as the dunes are, sand is somewhat of a minority of the surface. Just as well, it would be impossible to drive over the sand.

We got stuck in sand more than once, and had to dig, place sand mats, and push to get out. The road would often split into multiple parallel tracks and later recombine. But it generally all went one direction, north, and we only got lost temporarily once or twice.

Camping out was not without hazards. One morning Neil got up and when dressing, made the very painful discovery that a scorpion had crawled into his trousers at night. The sting laid him out for pretty well two days, one day in agony and one day sleeping it off. From then on we always checked for scorpions in clothing and belongings.

Water sources were difficult to find. We all had to ration our water. We could drink as much as we wanted from the tank, but each person was limited to a 2 litre bottle for washing and personal use. It became a source of pride to show what we could do with our allocation. One of our group showed off how he could have a full bath and wash his clothes all in a basin containing 2 inches of water.

We made the Niger border post Assamaka on 27 Sept, where we performed the usual exit rituals and had a wash in the camel trough. Just beyond, we met a convoy of vehicles coming south. A Renault R30 was stuck in sand so we pulled it out and continued on our way. After 13 days in Niger we crossed into Algeria.

Algeria

(Click for map)The border between Niger and Algeria is unmarked, therefore difficult to know exactly where we crossed. But a short distance farther was the nominal border settlement of In-Guezzam. It was here that we formally entered Algeria about 09.00 on 28 Sept. In-Guezzam was little more than a small garrison with a few military personnel and maybe a few civilians, a bleak lazy place where nothing ever happens. Near the buildings was a small well, probably the reason the place is here at all. We replenished the water tank as much as we could from the few inches of cloudy water at its bottom. In the office we saw a small collection of music cassette tapes. Being sick of our own ones by now, we tried, unsuccessfully, to trade some of our truck tapes for theirs.

Our camp stop locations were rather random, one place is pretty much like another in the featureless landscape. We made fires and cooked with firewood brought up from Niger, none being available here. At least the wood was dry and burned easily.

Some of us still used tents, but I preferred to sleep in the open with just a sleeping bag, sheet and mat. Even in wind storms it was quite comfortable. Murderously hot by day, the nights were pleasantly cool.

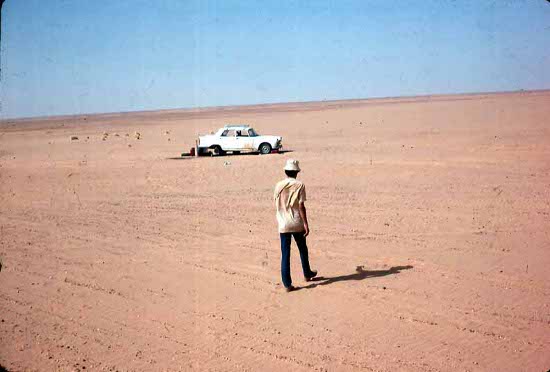

We weren't totally alone in the desert. This was one of the main highways between North and West Africa. We met truck convoys plying the road south, loaded up to incredible heights with goods, people riding atop the cargo. A few European travel expeditions also came past. We occasionally saw abandoned cars by the track, gutted and sand-scoured skeletons of vehicles that tried and failed the difficult journey.

Stranded, Sahara

At one point, in one of the most remote and featureless locations of the desert, we came across a lone Swiss guy sitting in his broken down Peugeot 404. We had heard about him in Agadez and were on the lookout for him. He had been in a convoy a week or two ago and his differential had broken on the road. Rather than abandon his car, he chose to stay with it and wait for parts to be sent up from Agadez. He asked us about progress on his car parts (no news as yet), and we asked him if he needed any water or food (he was OK for the moment). Why he hadn't gone mad yet we'll never know. I still wonder if he ever got going again, or is he there to this day?

One evening we stopped near a couple of rarely-seen trees to camp. Not long after arriving, an Algerian goods truck stopped nearby too. A whole desert, and they stop next to us, great. Anyway they didn't bother us and left early next morning.

At another camp stop in a long wide wadi, I took the opportunity to get away from the group and walk out alone into surrounding hills and dunes, at sunset an almost surreal feeling of vastness and isolation.

Four days from Agadez, the vast flat expanse of desert gradually gave way to rougher country. We were entering hills, dry wadis, rocky roads and outcrops. Remarkably there was some vegetation here and there, tufts of scrub and melon plants, especially where water may infrequently flow. We were entering the remarkable Hoggar mountain range, a spectacular geological formation virtually in the geographical centre of the desert.

The main settlement in the Hoggar is the windy, dreary, dusty town Tamanrasset, with a couple of stores, government buildings and homes. But in a mountainous and (extinct) volcanic area, it's the surroundings that give it its appeal. I bought some onions, potatoes and melons and tried to make lunch, but a wind storm put sand all over the meal.

We could have just stopped here and then continued on to Algiers. This was after all the day we were originally supposed to arrive in London. But Chris our driver knew about a place called the Assekrem about 80 km to the east, a slow 8 hour drive on a rough and steep road. At about 10000 ft altitude, it is the highest point in the Hoggar, and home to a small settlement and a hermitage monastery. Even though it was out of our way and we were late, he decided, to the great delight of us all, to allow a side trip there.

It was absolutely magical. The mountains on the way up were some of the most spectacularly rugged and beautiful I had ever seen in my life. We arrived at a small saddle at 15.30, a couple of brick buildings inhabited by Touaregs and an area to camp, maybe a hundred metres or so below the top of the mountain. Atop the mountain was the Hermitage, with possibly the world's best view.

In the late afternoon, before dinner, several of us went up one of the nearby cliffs for some rock climbing practice.

In the evening, a couple of our group accepted an invitation from one of the local families for tea in their house. It was allegedly a pleasant and interesting experience, although they had to politely decline an offer from the host to swap his wife for the girl for the night.

At the altitude, it was quite cool at night, the coldest place of our whole trip. But not bad enough that we couldn't sleep; I appreciated my sleeping bag that night.

Hoggar at Dawn

Next morning we were up before dawn. One of the main attractions of the Assekrem was the opportunity to walk up to the Hermitage of Pere de Foucald on the mountain top. This was Sunday morning and, in addition to the once-in-a-lifetime view of sunrise over the Hoggar, we could attend mass in a unique location. A half hour or so walk up the steep winding path in the dark, and the sunrise from the top was incredible. We gazed in awe as the yellow rays of the sun slowly illuminated the browns and greys of one peak after another; words fail me.

A few monks and the Father inhabited the hermitage. Mass was simple and spartan in the small rustic chapel, but replete with atmosphere.

As we admired the incomparable view, we could make out in the distance a southbound Exodus expedition truck gingerly making its way up the road in our direction. It eventually arrived at the campsite and the group spilled out and immediately started up the path to the top. We met them as we made our way back down, quite an experience meeting one of the few other expeditions on our trip. The truck was brand new and the group fresh-looking; we must have looked shocking in comparison.

The Hoggar, and especially the Assekrem, was undoubtedly the highlight both in altitude and in memory value, of my African expedition.

Back at the camp, we packed up for the trip back to Tamanrasset. The other group came with us and we camped together that night.

Next day, October 3, we filled the water tank and resumed the journey north. We had finished the unsurfaced track coming up from the south; from here on north the road is paved. Now we could make good time, and get through to Europe soon. Even I was starting to become conscious of the schedule, as I had friends to visit in Switzerland and England, and I absolutely had to get back to Australia in November before my 3 year re-entry visa ran out.

The first night out of Tamanrasset, camped in a sandy valley between hills, we were struck in the night by a brief but fierce sandstorm. Those who were using tents had them blown down on top of them, but I was OK sleeping in the open, just covering up to keep the sand out. I found a large, about 4 inches, beige-coloured spider, a camel spider I think.

We drove through Arak Gorge along a wadi with tabletop peaks on both sides. Then passed by Ain-Salah, the "City of Salt" without even slowing down, there seemed to be nothing there to stop for. Later we climbed onto the Plateau of Tademait, a vast, featureless, kibble-surfaced landscape.

At the next oasis town, El Golea, we could stock up on food in the markets. On the way out of town, our truck overtook a local guy driving his donkey and cart. We waved at him as we passed, and then started to laugh and cajole him by gestures of "C'mon, get a move on, we're ahead of you". Not to be outdone, he laughed back at us and proceeded to whip his donkey into a frenzied gallop to keep up. Great fun. Fortunately we picked up speed and receded in the distance before he managed to kill his poor beast.

We stopped briefly in another oasis town Ghardia, as its mosque blared out its call to worship. Shops, patisseries and activity tempted me to explore here. Butcher shops had real beefsteaks on display next to the ubiquitous chickens and goat heads. But, as we were nearing the coast we had to move on.

On through the towns Laghouat, Djelfa and Blida, the desert quickly gave way to hills with trees and grass. Beautiful gorges displayed eucalyptus trees and waterfalls, and vineyards and orchards abounded. A guy driving a bus with no windshield came up behind us waving and laughing. As he passed, he threw fruit, bread and eggs into our truck, good fun and feed.